George Washington was the first President of the United States. This is true, and we know it is true.

How is it true, and how do we know?

Here are ten quite different ways you could argue it is not true, or that we don’t really know:

One should never hold any belief with absolute certainty. We can say that “George Washington was the first President” is probably true, and we can use evidence to calculate that probability. However, it’s misleading and meaningless—or outright wrong—to claim that it’s simply “true.” One can only ever say “given such-and-such observations, the probability that Washington was the first President is 0.99” (or whatever the correct number is). If you are too lazy to do the math, then at the absolute minimum you must always explicitly acknowledge “this is probably true, but it could be false, too.”

The first President was John Adams, and no one questioned that at the time. In the 1830s, there was massive rewriting of history to justify Andrew Jackson’s coup against the Adams Dynasty. That was so successful that only a few historians—now dismissed as cranks—know the truth.

“Presidency” is an essentialist delusion. There is no set of objective features that correspond to “being President.” If you dissected Barack Obama, you could not find his supposed “President-ness” anywhere. The same would have been true of Washington. This is not merely a limitation in our knowledge; “Presidency” simply isn’t a physical property of some people. There’s no separate non-physical reality, so there’s no such thing as a “President.”

“Presidency” is a subjectivist delusion. It’s an objective fact that almost everyone believes Washington was the first American President. When we know more neuroscience, we’ll be able to find those beliefs with brain scans. But mere collective belief can’t make something exist; nearly everyone used to believe in ghosts.

Washington was the second President. You cannot step in the same river twice: because the river is never the same again, but more importantly because you are never the same person again. Likewise, you cannot elect the same person President twice. The first President (1789–1793) was also named “George Washington,” but he had not yet evolved into his final form. The true George Washington was President from 1793–1797.

George Washington no longer exists. Anything you say about a non-existent object is necessarily meaningless, not true or false. You might as well make claims about colorless green ideas.

“The United States” does not refer to a solid, distinct, changeless, clear, well-defined entity. The term is necessarily unclear in some ways, and the thing itself is necessarily somewhat nebulous. The phrase certainly meant something quite different in the 1700s than it does now. We cannot make durable, definite claims about fluid, indefinite entities.

Due to technical irregularities, Washington was not elected in full compliance with Constitutional procedures. Although he acted as if he were President, and everyone regarded him as President at the time, he actually wasn’t. The true first President, elected in full conformity with Constitutional requirements, was John Adams.

Although Washington was the first President de jure, William Howe earlier exerted sufficient authority throughout Anglophone America that he ought to be recognized as the first President de facto.

The Revolutionary War was an illegitimate rebellion against a legitimate government, and so cannot have established a genuine state. The British Crown remains the legitimate government of North America, and “The United States” is a propaganda fiction. America has never had a “President.”

Getting meta-systematic cognition wrong—and right

All these objections are silly and wrong.1 How and why?

Each uses some system of reasoning that, while sometimes valid and helpful, is worse than useless in this case. There’s nothing wrong with any of the systems; they are just wrong ones to apply here.

Judging whether or not a system applies is the simplest form of meta-systematic reasoning. Meta-systematic reasoning is the cognitive aspect of Kegan’s “stage 5”, the fluid mode, or the complete stance. (These are different terms for more-or-less the same thing.) I have suggested that broader understanding of meta-systematicity is currently critical to the survival of civilization, so I plan to be helpful by saying more about it. This post is a starting point—beginning with the simplest manifestation.

My hope is that the ridiculous examples start to give a sense of what “meta-systematicity” means. Eventually I hope to say much more, across many web pages. For now, perhaps some readers can extrapolate to other aspects of meta-systematicity, or even to the whole thing.

(Some other forms of meta-systematic cognition are figuring out how to apply a system in a concrete situation; combining systems, or parts of them; and creating new systems. Also: systems generally apply more-or-less well, and never quite perfectly, so the judgement is of whether a system applies well enough. For clarity and simplicity, in this post I analyze atypically silly examples in which a system fails to apply at all, or is drastically mis-applied, so the judgement can be quite definite.)

Judging is neither determining nor intuiting

“Judging” is a careful choice of word: it is neither “determining” nor “intuiting.” “Determining” would be systematic, and “intuiting” would be anti-rational.

Some systems come with systematic criteria for whether they apply. For instance, some programming languages can handle parallel processing, and some can’t. In such cases, we can definitively determine whether a system applies, using systematic rationality. Although that is reasoning about a system, it is not “meta-systematic,” in the sense I use the term. “Meta-systematic” means using systems in ways that are not themselves systematic.

Meta-systematic judgement is not some sort of Romantic intuition, mystical insight, or super-Turing woo. Often, it is easy. I made the ten objections deliberately ridiculous to show how obvious and down-to-earth it can be. Meta-systematic cognition does not reject either common sense or systematic rationality. In fact, it depends on both.

While it is easy to explain why each of the ten objections mis-uses a system, the reason each is silly is specific to it, and to Washington’s Presidency. The form of each objection is valid when applied to other claims. None of the objections is formally illogical. None is irrational according to any systematic theory of rationality.

What is hard is to say in general when a system of reasoning is applicable. Judging applicability is human-complete, in fact. By that, I mean that there is no aspect of human beingness that is not potentially relevant. (I do not mean that humans are somehow special, so that we can resolve questions of judgement by magic.)

Judgement cannot be reduced to any algorithm, or set of determinate criteria.2 In general, there is no end to the kinds of evidence and kinds of reasoning that might go into a judgement. Each has to be evaluated on its own, idiosyncratic merits. In many cases, this means that a judgement cannot be made, or can only be tentative. In others—such as the question of whether Washington was the first American President—a judgement can be quite certain.

This implies that epistemology is also human-complete. There can be no systematic “scientific method.” The best we can get is meta-systematic judgement among alternative lines of investigation.

That is a larger claim than I can justify in a blog post. However, I hope this post will help you see why it might be true.

Analyzing ten meta-systematic failures

The rest of this post goes through each of the ten objections and:

- explains what system is being misapplied;

- explains that it’s a perfectly sensible system that is often useful;

- explains why it doesn’t apply to Washington’s Presidency;

- begins to explain why its range of applicability cannot be specified systematically.

I won’t attempt to prove that any of these systems lacks systematic applicability criteria. An argument about that could be unboundedly complex and difficult—precisely because it’s meta-systematic, and therefore human-complete.

My discussions of applicability will be brief and vague; this post is quite long even so. For some of the systems, the analysis may still get more technical than you want to read. In that case, it’s safe to skip ahead to the next.

Among the ten objections, the first two are epistemological: they claim we have inadequate evidence to know that Washington was the first American President. The rest are ontological, concerning the fundamental nature of things. Objections 3 and 4 challenge the reality of meaningness: is there even any fact-of-the-matter about who the President was? The next three point out the fundamental nebulosity of all objects. And the last three rely on the nebulosity of social institutions specifically.

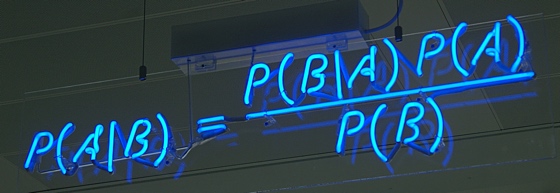

Bayesianism

One should never hold any belief with absolute certainty. We can say that “George Washington was the first President” is probably true, and we can use evidence to calculate that probability. However, it’s misleading and meaningless—or outright wrong—to claim that it’s simply “true.” One can only ever say “given such-and-such observations, the probability that Washington was the first President is 0.99” (or whatever the correct number is). If you are too lazy to do the math, then at the absolute minimum you must always explicitly acknowledge “this is probably true, but it could be false, too.”

This is a misapplication of probabilistic reasoning.

Probability theory is one of the most valuable systems of formal rationality. It is central in many fields of science, engineering, medicine, economics, business strategy, and public policy analysis. Everyone should learn the basics of probabilistic reasoning in high school.

Probability theory is also completely useless in most everyday situations, and also in many fields of science, engineering, and so on. In the case of Washington’s Presidency, attempting to compute a probability would be completely meaningless. Also, it is so close to 1.0 that even if it could be computed accurately, it wouldn’t be useful. Most of the time, trying to reason probabilistically is dumb.

Under what circumstances is probability theory useful?

Some things—like Washingon’s Presidency—are too certain. Most things are too uncertain. I started laying the groundwork for a broad analysis of “too uncertain” in “Probability, knowledge, and meta-probability” and “Probability and radical uncertainty,” but unfortunately haven’t gotten around to finishing that sequence of posts.3

Applicability can’t just be reduced to a restricted range of degrees of certainty, however. In “How To Think Real Good,” I suggested that there are many different kinds of uncertainty. Any particular situation typically involves several, some more amenable to probabilistic modeling than others. This makes questions of whether and how to apply probability theory complex.

I have a draft post on judging when probability theory will work. (This might help un-stick those who want to believe it’s always the answer to everything.) What features of a situation allow you to assign meaningful probability estimates? There are many heuristic considerations that can go into that judgement. Recognizing these can be valuable in practice. On the other hand, they are necessarily vague, domain-dependent, and unbounded. (Nebulous, in other words.) There can be no precise, general, systematic answer.

A recent satire of Bayesianism turns on this unboundedness. Applying probability theory requires circumscribing the hypothesis space (as I explained in “How To Think Real Good”), and there is no systematic way to do that.

Historical fabrication and revisionism

The first President was John Adams, and no one questioned that at the time. In the 1830s, there was massive rewriting of history to justify Andrew Jackson’s coup against the Adams Dynasty. That was so successful that only a few historians—now dismissed as cranks—know the truth.

It’s widely known that Washington wore false teeth, made of wood. This is false; none of his dentures were made of wood.

It is also widely known that the story about young George and the cherry tree is a myth. The fable was generally accepted as fact during the 1830s, however. Even now, it is not widely known that it was fabricated by a historian, in 1806, to promote a particular political program.

It is widely known that Buddhism is the religion taught by the historical Buddha, named Siddhartha Gautama, who lived about 2500 years ago. This is false. There is no good historical evidence of Gautama’s existence. If he did exist, there is insufficient evidence to determine what he taught. We do know for sure that most of Buddhism was not taught by him, because it can be reliably dated to much later eras. Most of “Buddhist history” has been shown by recent mainstream scholarship to have been fabricated, in various centuries after the supposed events, to justify then-current political movements.

This is closely parallel to the claim that Washington’s Presidency was fabricated to erase from history the Adams family’s hereditary monarchy. It’s just that Gautama’s teaching was invented later, and Washington’s Presidency wasn’t. How do we know?

Some details of what mainstream experts currently believe about Washington may be wrong, because they have mistakenly accepted evidence from fabricated historical documents. I hope you will agree, though, that it is not meaningfully possible that his entire Presidency was fabricated. How do we know?

There’s two questions here, actually: how do historians know, and how do we know that they know? This is an instance of socially distributed knowledge. We do know Washington’s Presidency couldn’t have been fabricated, but we know that only in dependence on a community of experts. No single historian knows independently, either; each of them depends on the rest.

Professional historians use a wide variety of technical methods for evaluating different kinds of evidence, and coming to conclusions based on them. All these methods involve judgement, however. You cannot systematically assign a numerical “strength of evidence” to a hand-written letter signed “Geo. Wash.”, a painting of the First Inauguration, and a 1794 newspaper article, add it up and declare “p<0.05: we know.” There is no end to the considerations that might be relevant to whether any such things may have been faked. In some cases—including this one—rational certainty can be reached, however.

(By the way, the painting at the head of this page is supposedly of Washington’s First Inauguration in 1789. It hangs on the wall in Federal Hall. However, reliable-sounding sources suggest it was painted a century later, in 1889, by one Ramón de Elorriaga. Other reliable-sounding sources suggest that this attribution is dubious, so maybe no one knows where the painting came from. Based on a casual web search, it seems that there is no surviving depiction of either of Washington’s Inaugurations that was created within his lifetime. I’m not sure, though!)

The question of how we know the experts know is still more nebulous—although no less certain. Entire professions full of mainstream experts can be totally wrong, as in the case of nutrition. I personally know almost nothing about what sort of evidence for Washington’s Presidency is available for professional historians. Instead, my judgement is that if there were any meaningful chance that they were wrong, I would know about it. It is hard to say what that judgement rests on, though!

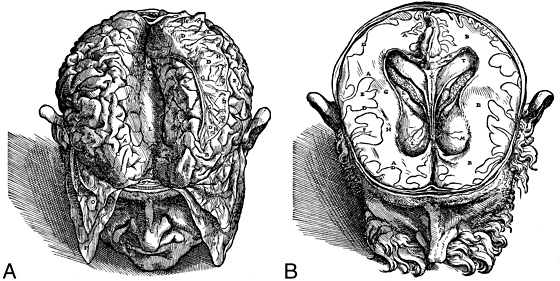

Essentialism and inherent (or objective) meanings

“Presidency” is an essentialist delusion. There is no set of objective features that correspond to “being President.” If you dissected Barack Obama, you could not find his supposed “President-ness” anywhere. The same would have been true of Washington. This is not merely a limitation in our knowledge; “Presidency” simply isn’t a physical property of some people. There’s no separate non-physical reality, so there’s no such thing as a “President.”

Essentialism is a ubiquitous metaphysical error. It features in theories according to which meanings are objective, or inherent in the things that have the meaning. It is closely related to eternalism, and is harmful for many of the same reasons.

One current manifestation is the increasingly acrimonious debate over whether trans people are male or female. Most participants, on both sides, agree that trans people are inherently, objectively, essentially one sex or the other. They only disagree about which sex that is, and what the criteria are for determining this objective truth! This seems plainly wrong to me. Sex (like everything) is somewhat nebulous. There are irreducible gray areas. Insisting that there is a clear-cut objective fact about whether some people are male or female is politically-motivated metaphysical nonsense.

On the other hand, vacuum cleaners do objectively, inherently suck. If you disassemble one you can see how and why. And in most cases, it’s clear what sex someone is, in ways that depend largely on physical facts, not social agreements. However, there is no sharp boundary between the gray areas and the clear-cut cases. One might say that “transness” is a matter of degree, and continuously graded; but even that would be a gross oversimplification.

Back to Presidency. The “dissection” objection is quite right that it is not an objective, inherent property of a person. This is an important point. I will make a similar argument in “A billion tiny spooks,” against the claim that knowledge is an objective, inherent property of a person. The representational theory of mind says that my knowing Washington was the first President consists of having that written down in my brain somewhere. This can’t be true, partly because (as I wrote above) that knowledge is socially distributed.

But then what? The following objection points out, also correctly, that Presidency is not a matter of subjective agreement. If Presidency is neither objective nor subjective, that might seem to cover all bases. And if it is not a property of an individual, nor a social agreement, what sort of a thing could it be? Should we conclude that it does not exist?

One could say that “Presidency” exists “in the domain of meanings”—although that is also misleading. The book will eventually explain how meanings can be neither objective nor subjective, but real just the same. They are also not non-physical, or “mental.” They are non-local interactional dynamics.

The subjective theory of meaning

“Presidency” is a subjectivist delusion. It’s an objective fact that almost everyone believes Washington was the first American President. When we know more neuroscience, we’ll be able to find those beliefs with brain scans. But mere collective belief can’t make something exist; nearly everyone used to believe in ghosts.

When the objective, correspondence theory of truth started to break down, philosophers advocated various alternatives. One was the consensus theory, that truth is simply a matter of agreement. In the case of physical facts, this is obviously idiotic. (Although some “spiritual” people do still apply it.)

In the domain of meanings, the consensus theory is also wrong, but less obviously so. It is common for otherwise-intelligent people to explain social institutions as “collective hallucinations.” A hallucination means a mistaken perception of something that is not really there. But are we mistaken to believe that there is such a thing as a President? Clearly not.

Nevertheless, the objection is right that everyone believing someone is President does not make him so. Let’s say John Adams XIV, the popular Party Planner of the college Glee Club, was voted in as President of the Club. Naturally, everyone (including John XIV) believed he was President. A few months later, the Treasurer discovered that, in XIV’s former Party Planner role, he had been skimming cash from the amounts entrusted to him for beverage purchase. Clearly he had to be removed as President, but no one knew off-hand what the official way to do this was. Someone remembered that the Club had an ancient set of bylaws, which no one had looked at in years. Reading through them carefully, the Club’s other officers discovered that the section on elections stated that the winner of an election was the person who got the most votes, unless they had committed “moral turpitude in respect of the purposes of the Club.” Embezzlement is mentioned as an instance of “moral turpitude.” Under the wording of the bylaws, it’s irrelevant to the election outcome whether anyone knew about it—only that it had happened. Thus, XIV had never been President—even though everyone had thought he was.

Beliefs play important roles in most meanings, and most social institutions. However, they don’t fully constitute either. The roles beliefs do play are generally complex, nebulous, and not understandable in systematic terms.

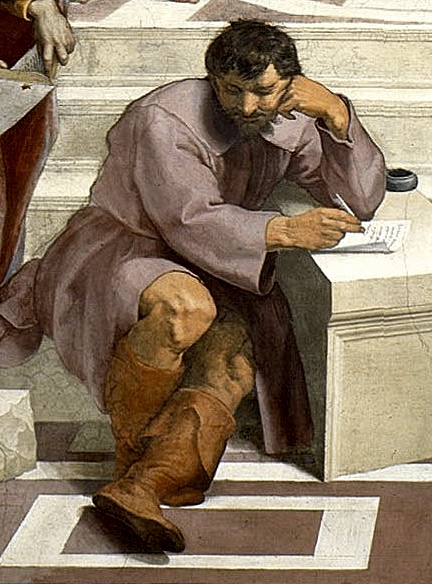

Transtemporal identity

Washington was the second President. You cannot step in the same river twice: because the river is never the same again, but more importantly because you are never the same person again. Likewise, you cannot elect the same person President twice. The first President (1789–1793) was also named “George Washington,” but he had not yet evolved into his final form. The true George Washington was President from 1793–1797.

“The same river” is a theme of the Pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus, who emphasized constant change. Famously, he said “πάντα ῥεῖ”: everything flows. But what he said about the river was more complicated than usually remembered:

Ποταμοῖς τοῖς αὐτοῖς ἐμβαίνομέν τε καὶ οὐκ ἐμβαίνομεν, εἶμέν τε καὶ οὐκ εἶμεν.

We both step and do not step in the same rivers. We are and are not.4

When has something changed enough that it is no longer the same thing? This is the problem of transtemporal identity. Another ancient Greek formulation is “the ship of Theseus.” Suppose that, as a result of a series of repairs, every board in the boat is eventually replaced; is it still the same one? Suppose the ship’s carpenter saved all the worn boards and later assembled them into the same form as the original ship (albeit rather beaten-up-looking). Would that be the same boat? It is and it is not.

There can be no general, systematic, or definite answer. There is no fact-of-the-matter about whether the Truckee River is the same river today as when I stepped in it last week. There is no fact-of-the-matter about whether I am “the same person” today as when I stepped in it last week, or when I first did decades ago. Same in what way?

Nevertheless, we can often make judgements about whether something is the same thing for particular purposes. Although no systematic criteria apply, we can say quite firmly that it’s silly to claim that the President of 1789 was not the same person as the President of 1793.

Positivism

George Washington no longer exists. Anything you say about a non-existent object is necessarily meaningless, not true or false. You might as well make claims about colorless green ideas.

“Positivism” is a vague term. It is often described as “the rejection of metaphysics.” The general idea is that we can gain knowledge only from sense data (observations and measurements) and from reasoning about those data. The main motivation was to reject religious claims about non-existent objects such as God, souls, and Heaven. In general, this is sensible and right. You might as well say “colorless green ideas sleep furiously” as “the Holy Ghost proceeds from God the Father.” Both are meaningless—in some sense—because they refer to objects that we can’t observe and therefore don’t exist.

However, no one has been able to make positivism into a coherent system. The logical positivism of the early 20th century said all statements were unambiguously true, false, or meaningless, and ones about non-existent objects were definitely in the third category. This makes sense, but fails on some examples.

George Washington does not exist—not in 2016. We cannot observe or measure him. Accordingly, some positivists backed themselves into the corner where they were forced to say that statements about past objects are meaningless. This, obviously, is silly—but it’s hard to explain precisely why.

I said that none of the ten objections were formally irrational. Might this one be an exception? There is no logical fallacy, but one could reasonably argue that a metaphysics of transtemporal predication must be part of any general theory of rationality. On the other hand, I don’t know of any credible account. (Dealing with the problem of transtemporal identity would be only one of several difficulties.)

In fact, we don’t have any general theory of rationality. Logical positivism was the last serious attempt to develop one. By the 1960s, it had unambiguously failed, for several reasons, any one of which would have been fatal.

There is another slippery slope here. George Washington does not exist, but it is straightforwardly true to say that he was the President. Gandalf does not exist, but it is true—in some sense—to say he was a wizard.5 This is a meaningful sense, because it is definitely false to say he was a BMX freestyle rider. That we can make definitely false statements about Gandalf does imply we can make meaningfully true ones too. Unfortunately, this suggests “the Holy Ghost proceeds from mayonnaise” is definitely false, which suggests that “the Holy Ghost proceeds from the Father” is also true in some sense. Unfortunately, we cannot exorcize spooks just by declaring all statements about them meaningless. On the other hand, “the Holy Ghost proceeds from the Father” is definitely silly.

Much as we might like to, we can’t eliminate metaphysical considerations from judgements of system applicability. And those get complex and ambiguous fast—even in as mundane an activity as making breakfast.

The nebulosity of institutions

“The United States” does not refer to a solid, distinct, changeless, clear, well-defined entity. The term is necessarily unclear in some ways, and the thing itself is necessarily somewhat nebulous. The phrase certainly meant something quite different in the 1700s than it does now. We cannot make durable, definite claims about fluid, indefinite entities.

This is a misapplication of the nebulosity-and-pattern framework described in Meaningness!

According to that framework, nothing, even a steel ball, is perfectly solid, distinct, changeless, clear, or well-defined.6 Much less so a country. The United States is unquestionably intangible, fuzzy, changeable, vague, and ambiguous.

In fact, the ontological status of a state is deeply mysterious. We think we know what sort of thing a steel ball is: a “macroscopic physical object.” What that means is more mysterious than you might suppose, but at least we have a word for it.

What is a country? Maybe it is a “social institution,” which somehow lives in the intangible realm of meanings. But a country also has a geographic extent, unlike institutions such as a glee club. That geographic extent, nevertheless, is somewhat vague. As you can see from the map above, the boundaries of the United States were unclear in 1789, and have changed frequently since. Even now, its boundaries are disputed, and there are many places that are part of the United States for certain purposes and not for others. Puerto Rico and Guantanamo Bay are two quite different examples.

The transtemporal identity of countries is even vaguer than that of rivers or people. China, like the ship of Theseus, was disassembled in its 1949 Civil War, and the pieces reassembled into the Republic of China (“Taiwan”) and the People’s Republic of China, which may or may not be two different countries, either or both of which may or may not be the same country that existed before 1949.

For those of a positivistic bent—and I include myself in that category—it’s tempting to throw up our hands and say “states are collective hallucinations; they are metaphysical spooks; they don’t really exist.” But this is nihilism, the denial of meanings that are plainly evident. Denying the existence of the United States is silly.

“We cannot make durable, definite claims about fluid, indefinite entities” is often importantly true. Social justice is a standard example. It is not meaningless and not non-existent, but it is highly nebulous. Claiming that social justice has unchanging and absolute implications is a common move in current political discourse, but it is usually silly. It is a form of eternalism, and specifically the eternalist ploy of imposing fixed meanings. That is harmful.

Granting the existence of the United States, and granting that it is fluid and indefinite, can we make durable and definite claims about it? Yes. “Washington was the first American President” is a durable claim: it will still be true in a thousand years, even if the United States has ceased to exist. It is a definite claim: it was George Washington who was President, not Martha Washington, and not George William Frederick.

So when can we make durable, definite claims about fluid, indefinite entities, and when can we not? That is a matter of judgement, and unbounded considerations may be relevant.

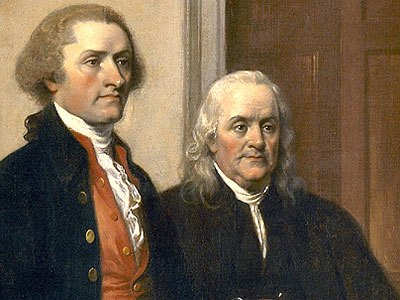

Strict constructionism

Due to technical irregularities, Washington was not elected in full compliance with Constitutional procedures. Although he acted as if he were President, and everyone regarded him as President at the time, he actually wasn’t. The true first President, elected in full conformity with Constitutional requirements, was John Adams.

This is probably factually false; I just invented technical irregularities in Washington’s election.7 That’s not its main problem, though. It’s a misapplication of strict constructionism, the idea that the only thing that counts is what the Constitution says. If there had been a minor procedural glitch in Washington’s election, it wouldn’t matter. But there are many cases in which technicalities do count. Discovering them may reverse the result of an election that had been thought settled—as in the case of John Adams XIV.8

Thomas Jefferson was one of the first advocates of strict constructionism. His Republican Party opposed the growing power of the national government, and supported state’s rights. The Constitution says that:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

Jefferson argued that it meant what it said, and the United States could not do anything the Constitution did not specifically say it could. His former friend John Adams, a Federalist, argued that the Constitution implied powers it didn’t expressly mention.

Both positions are reasonable, but seem incompatible. The bitter election of 1800 pitted the two men against each other as candidates for President—and their Constitutional interpretation philosophies against each other as candidates for the national political ideology. This election was marked by multiple technical irregularities. It was also perhaps the most divisive in American history. Jefferson feared that Adams intended to found a hereditary monarchy; Adams feared that Jefferson intended to break up the Union. Both may have been right.

Strictly strict constructionism is actually impossible.9 Laws are not like computer programs, which causally engender exactly the computations they describe. There is no such thing as an entirely literal and context-free meaning of a text; human languages doesn’t work that way. Applying anything written in a human language always, necessarily, requires interpretive judgement in a concrete situation. Interpretation always, necessarily, depends on unbounded considerations, and so cannot be reduced to a system.

Nevertheless, some legal interpretations are more literal, and others more contextual. In practice, courts have to steer between the Scylla of literalist myopia and the Charybdis of judicial activism.

So, when do electoral technicalities count? Why should we apply a “strict” standard to John Adams XIV and a “contextual” one to George Washington?

This is a judgement, for which an unbounded set of considerations may apply. There can be no systematic answer; one can only say that most of the considerations, or the stronger considerations, point one way or the other. Here are a few, offhand, in this case:

The Electoral College’s vote was unanimous both times Washington was elected. If a procedural error had been found and the vote repeated, we can be reasonably certain Washington would have won again. We can be reasonably sure that if a new vote were held, John Adams XIV would lose. In neither case is there any legal basis for a re-vote, but the outcome of the thought experiment is a relevant consideration.

The system under which Washington was elected was brand new, and unlike anything that had been tried elsewhere.10 Complicated new systems inevitably have minor bugs, which get ironed out quickly with experience. In a new system, the designers’ intent matters more than texts or precedent. There is no question that the writers of the Constitution wanted Washington as President. On the other hand, in a long-standing system that is known to work generally well, stability is more important than the designers’ intent, which may be forgotten or irrelevant to new conditions. The Glee Club bylaws were “ancient” and also were probably similar to those of similar organizations; they can be assumed to have been mainly debugged and therefore functional.

The stakes were much higher in Washington’s case than John XIV’s. Doubts about whether Washington was actually President could easily have torn the Union apart. (Consequences count.) Washington acting as President of the United States (whether he “really” was or not) was enormously significant; XIV acting as President of the Glee Club was not.

Indeed, Washington in part defined what it means to be an American President, by example. He was elected to an office whose nature was only vaguely specified in the Constitution. The Electoral College mostly just wanted him in charge; they elected a person, not an official.

None of these is a strong argument; but taken together, I think the case is reasonably clear.

(Before we move on: the story of Adams and Jefferson’s friendship, their subsequent enmity, and their eventual reconciliation is fascinating. Here is a brief account. The two men both died on July 4th, 1826, fifty years to the day after the signing of the Declaration of Independence that they co-wrote. This must mean something.)

De jure and de facto

Although Washington was the first President de jure, William Howe earlier exerted sufficient authority throughout Anglophone America that he ought to be recognized as the first President de facto.

The de jure/de facto distinction is key to understanding systematic social institutions. A non-systematic institution (such as a hunter-gatherer band) has no de jure aspect; a systematic one does, by definition. However, every systematic institution also has a de facto aspect, which is more or less discordant with the de jure one. The relationship between the two is always nebulous: complex, variable, and ambiguous.

To understand a systematic social institution, you have to analyze both aspects, plus their relationship. It is often true, though, that the de facto aspect is the one that primarily matters. For example, the de jure Constitution of Syria states that “The political system is based on the principle of political pluralism, and rule is only obtained and exercised democratically through voting,” but the facts on the ground suggest otherwise.

It is not uncommon for someone to be President de facto but not de jure, for any of several reasons. For instance, if the de jure President is non-functional, but it would be inconvenient to remove them from office de jure, someone else may do the job de facto. Some mainstream historians consider Edith Wilson to have been the de facto President of the United States for a year and a half, after her husband Woodrow’s incapacitating stroke.

Another common reason is that the supposed country of which someone is de facto President is new, and only a de facto entity itself. Leonid Tibilov is currently described as the “de facto President of South Ossetia” because South Ossetia is only a “partially recognized state.” De jure, it is nebulous whether South Ossetia even exists, and de facto it is nebulous whether it is a genuine state or a Russian puppet. However, Tibilov exerts sufficient authority throughout the territory of the supposed state that he ought to be recognized as the de facto President.

Similarly, perhaps, William Howe? He was Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in America from 1775 to 1778. It is nebulous whether the United States existed then either de jure or de facto. However, Howe was the most powerful man in America for much of the period. Should he be considered de facto President?

No, that would be silly. But why? You will now be unsurprised to hear that this is “a matter of judgement, with unbounded considerations that may be relevant.” Here are some:

The American President is head of government, and subordinate to no one other than the citizens collectively. Howe was several levels down in the British military chain of command, which was in turn subordinate to Parliament and the King.

Although the American President is Commander-in-Chief, the Presidency is primarily a civil, not military, office. Howe made no attempt to run a civil government; his activity was purely military.

Britain, and so Howe, did not recognize a unified political entity in North America, only a collection of colonies. Howe couldn’t hold an office, even de facto, in an entity that neither he nor his superiors considered to exit.

The term “President” was rarely, if ever, applied to heads of governments before the office was created by the United States Constitutional Convention, a decade after Howe left. Calling him “President” would be anachronistic. If Howe were considered de facto head of an American government, he should be called a “Prince” or “Governor” or something.

“Left as an exercise for the reader”

The Revolutionary War was an illegitimate rebellion against a legitimate government, and so cannot have established a genuine state. The British Crown remains the legitimate government of North America, and “The United States” is a propaganda fiction. America has never had a “President.”

This is the last of the ten objections. At this point, the pattern of analysis should be clear. If you’ve followed the story so far, you can probably work this one out yourself!

- 1.They are also fun; it’s tempting to add to the list. Maybe you’d like to do that in the comments?

- 2.You might object that every human, being a bounded volume of spacetime, is fully described by physical laws, and therefore algorithmic and systematic. This is arguably true, but not in an interesting or relevant sense. This post does not explain what I mean by a “system,” because that would be a long story. Roughly, I mean something humans can reason with. A particle-level specification of a macroscopic quantity of matter is not that. An algorithm, by some definitions, is “an effective procedure.” An “algorithm” that consists of a Unified Theory of fundamental physics plus the quantum state of a person is not meaningfully effective, even if it fits the mathematical definition.

- 3.Partly because LessWrong imploded. Maybe I should finish them here?

- 4.I suspect it is not by coincidence that this sounds like Nagarjuna, and like Zhuangzi.

- 5.The sense in which “Gandalf was a wizard” is true is not particularly mysterious. Presumably it’s possible to patch positivism to handle this case. I’m not trying to disprove positivism here, only to use “all statements about Washington are meaningless” as an obvious example of mis-applying the system.

- 6.These five characteristics are the fixations of the five aspects of form (pattern) according to Vajrayana Buddhism. I’ve alluded to the Buddhist framework for historical and humorous reasons only. The five-fold structure is a surprisingly useful heuristic, but is not seriously included in the Meaningness analysis of nebulosity and pattern.

- 7.I don’t know that there weren’t any, though. It wouldn’t surprise me if some are well-known to historians. It also wouldn’t surprise me if the process was so poorly documented that no one knows if there were any or not. I haven’t bothered to look into this, because (as I will explain) it doesn’t matter.

- 8.There’s an entertaining, although silly, argument that David Rice Atchison was President for one day in 1894, due to a procedural glitch.

- 9.And “strict constructionism” is not well-defined itself. It’s related, in ill-defined ways, to several similar ideas: textualism, originalism, and judicial restraint. None of those is well-defined either. These are important and useful concepts nonetheless.

- 10.With the interesting, but dubious, possible exception of the Iroquois Constitution.